CODESIGN AND COHOUSING: Creating Better Places Together

Introduction

The UK Cohousing Network’s summit delved into codesign and cohousing, fostering collaboration, sharing practices, and forging alliances for future initiatives. Through case studies, roundtable discussions, panels, and debates, participants explored how codesign operates within cohousing models. The event brought together a diverse group, including practitioners, policymakers, and designers from the Netherlands, England, and Wales, who engaged with residents, architects, developers, funders, and housing association staff. Participant feedback highlighted the summit’s value and success.

Cohousing experts emphasise that incorporating codesign in the pre-development phase is crucial for delivering long-term benefits to residents after they move in. But how exactly does this process work? What constitutes best practice? And, with the government planning to build 1.5 million new homes, could this approach influence more mainstream placemaking efforts?

Speakers and Contributors

Katerina Alexiou (Open University)

Jonny Anstead (TOWN)

Dinah Bornat (ZCD Architects)

Meredith Bowles (Mole)

Maria Brenton (UK Senior Cohousing Ambassador)

Clare O’Connell (Imagine IF Space)

Sam Goss (Barefoot Architects)

Mellis Haward (Archio)

Vera Hale (Open University)

Owen Jarvis (UK Cohousing Network)

Lewis Kinch (Southern Housing)

Flip Krabbendam (Architect NL)

Tijmen Kuyper (Cohousing Design Advice NL)

Jon Lee (Consultant, Wrigleys Solicitors)

Harry Randhawa (Triangle)

Emma Ridge (Wrigley’s Solicitors)

Sophia De Sousa (The Glass-House)

Louise Dennyson (The Glass-House)

Theodore Zamenopoulos (Open University)

Boris Zeisser (Natrufied NL)

Sponsors

“Housing: if it doesn’t work socially, then what is the point?” – Chuck Durrett

Owen Jarvis, CEO of the UK Cohousing Network, reflected on last year’s summit, where keynote speaker Chuck Durrett posed a challenge: how many of us live in high-functioning neighbourhoods built on trust and mutual support, fostering resilience among neighbours? Drawing on his experience of designing over 50 cohousing schemes and a strong foundation from working alongside Danish cohousing pioneers, Durrett emphasised that the quality of codesign is directly linked to the quality of community life after residents move in. This year’s event built on that insight, focusing on lessons from UK practitioners in codesign and cohousing and exploring what these practices can teach us about improving placemaking.

With the UK government planning 1.5 million new homes across new towns and sites, the familiar trade-off between speed, cost, and quality remains. Yet, Housing Minister Matthew Pennycook has publicly stated that placemaking quality is a key priority.

“This government is as ambitious about quality and design as it is about quantity.” Minister of State for Housing and Planning, Matthew Pennycook

Homes England has shown interest in cohousing, with two schemes announced for the next phase of the Northstowe new town in Cambridgeshire—an area previously criticised for lacking community spirit and infrastructure. Among UKCN’s members, there are 11 new builds, 15 retrofits, and 60 cohousing projects in development, with thousands on waiting lists eager to rent or buy into these communities.

Where Does Community-Led Housing Fit in the Policy Landscape?

The UK Cohousing Network is advocating for investment in what it terms the “4th Delivery Arm” of housing. This approach promotes “self-commissioned housing,” encompassing community-led projects like cohousing, self- and custom-build initiatives, and local SME builders. The aim is to complement the existing delivery arms—private, public, and non-profit (housing associations and large charities)—by empowering citizens and communities to take a more active role in solving housing issues, while supporting local builders to increase supply. Cohousing, a form of collective, resident-led custom build, exemplifies this model.

The call for a “4th arm” builds on the 2023 Bacon Review, which highlighted the untapped potential in custom and self-build housing, accounting for just 7% of new homes in the UK, compared to over 40% in many European countries.

The UK Cohousing Network is calling on the government to grow community led developments by:

1. Provide long-term financing,

2. Establish a community-led housing growth lab to scale delivery,

3. Implement policy reforms with a focus on community needs.

Leaders from the Community-Led Housing sector will meet Housing Minister Matthew Pennycook on 21st October to present their case.

Placemaking: the case for cohousing, Jonny Anstead (TOWN)

TOWN is a profit-with-purpose developer focused on residential-led mixed-use developments in the UK, with a mission to build better places for better lives.

Jonny Anstead discussed the challenge of scaling their work in areas without an existing community—a key element of traditional cohousing models. This sparked a debate about whether cohousing can be both community-led and developer-led simultaneously. Anstead shared the case of Marmalade Lane, the UK’s first “land-first” cohousing project, completed in 2018. In this model, the local authority owned the land and designated it for cohousing, after which the community was formed to develop the project. TOWN is working on similar projects, including Still Green in Milton Keynes, Angel Yard (a multigenerational cohousing project in Norwich), and two new schemes in Northstowe, Cambridgeshire. A post-occupancy report on Marmalade Lane reviewed its impact on residents over five years, using surveys, community engagement, and social value measurement tools to assess benefits for both people and the environment and include:

Neighbourhood and Belonging: Residents acquire a sense of community.

Convenience: Creating a one-minute neighbourhood.

Carbon, Energy, and Resources: Embedded in cohousing.

Learning: People share their skills.

Childhood: Children benefit from the presence of a community, yet developers often think more about bins than children.

Connection to Nature: Creating green spaces and shared gardens.

Health and Wellbeing: Residents stay active.

Cost of Living: Reduced through shared services (e.g., guest bedrooms).

Wider Community Benefits: Positive effects extend to surrounding communities.

Jonny Anstead says TOWN is exploring how to scale their cohousing work—can they create more developments without relying on a pre-existing group? In Jonny’s view, the UK needs a more diversified housing sector with more SMEs and experimentation. Policies must align the national housing agenda with the local vision. Demonstrating social value is key to showing potential landowners, councils, and policymakers the long-term benefits of these projects. Two upcoming cohousing developments illustrate this:

Northstowe:

TOWN has been commissioned by Homes England to conduct a feasibility study for a 40-home cohousing community and is currently recruiting members.

Linmere:

TOWN has agreed Heads of Terms with Land Improvement for a cohousing plot and will recruit a group over the next six months, with co-design to begin in March 2025.

Homes England is backing these cohousing projects not just for the benefits they bring to residents, but for their positive impact on the wider community.

Homes England were motivated to commission two cohousing schemes with TOWN, not only because cohousing is good for the residents who live there, but because cohousing is good for the areas and communities in wihch they are located.

Codesign for Housing: Insights from Mellis Haward,, Archio Ltd

Archio is an architecture studio focused on creating a better quality of life for all. They collaborate with local authorities, cohousing groups, community land trusts, and work on large-scale housing strategies and retrofits. Notable projects include *Citizen House* with London CLT, *Angel Yard* intergenerational cohousing in Norwich, and *Phoenix Lewes* hybrid cohousing with Human Nature.

Their approach centres on working closely with communities. As Mellis puts it, this requires architects to “leave their ego at the door” and prioritise collaboration with future residents. In codesign and cohousing, architects help navigate pros, cons, and complexities to reach consensus on key decisions, such as common house placement, privacy levels, and sustainability goals.

Archio has also produced two significant guides to support this work.

1. They have worked with GLA on a guide to commissioning codesign.

2. They have also produced the codesign toolkit, where they share what are the principles of codesign and how they relate to cohousing.

Some key principles mentioned

Setting a clear process: Giving people agency to get involved, e.g., through a flowchart that outlines the process step by step.

Giving others the pen: Using experience mapping to understand their perspectives, e.g., block modelling.

Enabling representative and constructive conversations: Building diverse networks.

Facilitating decision-making: Using exercises like temperature checks or traffic light systems (like, dislike, maybe) or cost prioritisation workshops.

Empowering communities long-term: Sharing knowledge through templates

Working with Phoenix Cohousing on a potential site (Lewes case study), Meillis faced the question of how a community can manifest what they want if there is not yet a cohousing community. Therefore, they created a festival workshop to create interest and appetite for sharing living, and to have clear principles of shared living.

Ongoing codesign, the architects/designer role continues after the community has moved in (though obviously it’s challenging capacity-wise). This can help understand:

o What has and hasn’t worked?

o What have they changed?

Something to be very clear is that public engagement is not the same codesign.

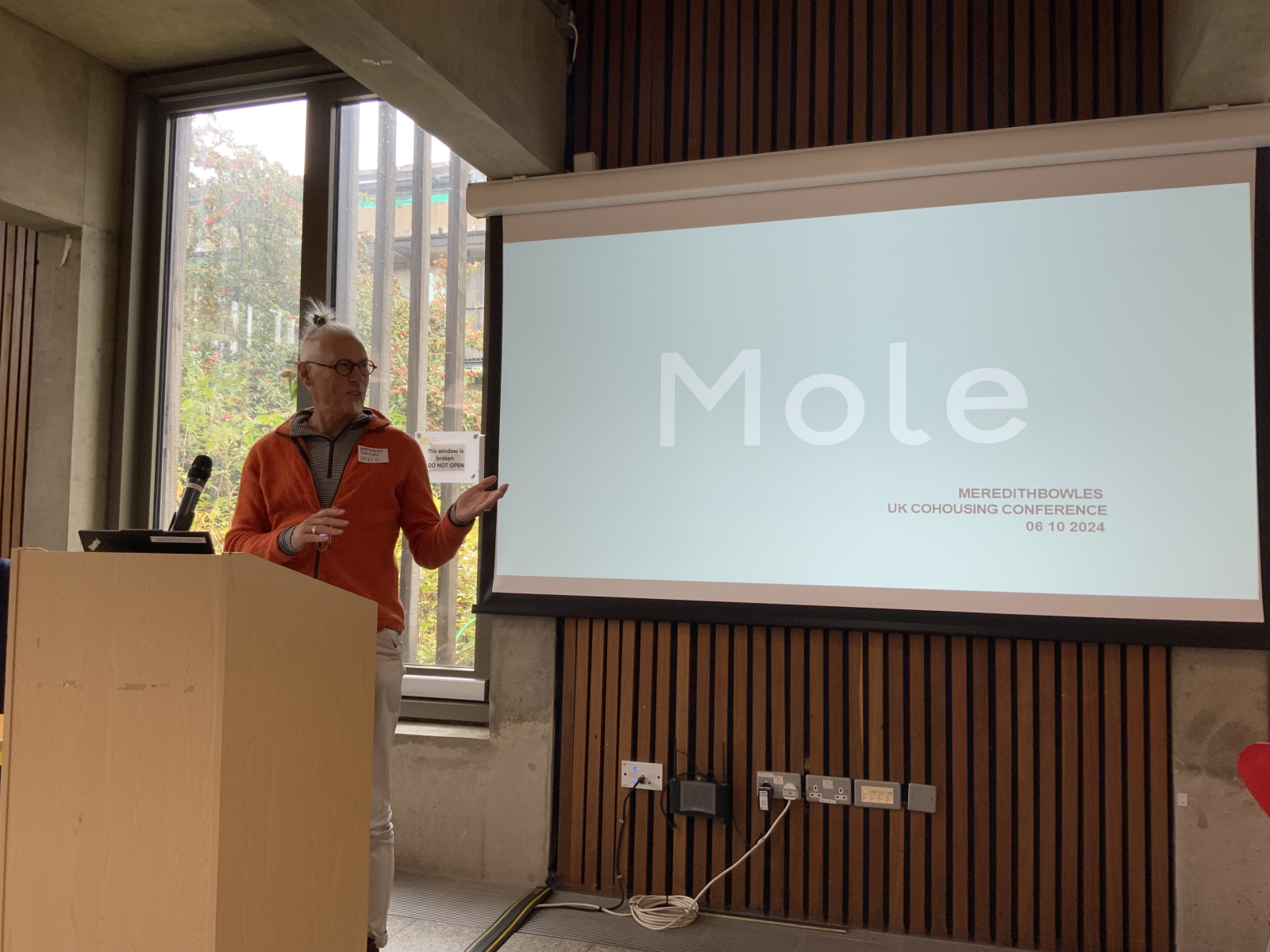

Codesign for housing, insights: Meredith Bowles, Mole Architect

Meredith presented the “Building Group Handbook”, a guide on collaborative design inspired by the German Baugruppen model—adapted for the UK market. Mole worked on the *Still Green* cohousing project in Milton Keynes, where 29 cohousing apartments were integrated into a larger scheme. The project faced advanced stages and significant constraints, so a complete redesign wasn’t possible. However, codesign helped clarify the group’s priorities within those limits, such as ensuring 100% accessibility in the flats. The process involved seven workshops, each with a specific focus.

Meredith also shared his experience working on “Amaravati”, a Buddhist monastery housing 50–70 people from around the world in a cohousing setting. Buddhist communities, like cohousing, share common values and make collective decisions. Key elements of the codesign process included:

Key aspects of the codesign process included:

· Ensuring the community understood what decisions would be made and when.

· Providing feedback after each workshop through one representative.

· Six workshops focused on specific topics, with a debrief and consensus explanation after each.

· The process helped them define their long-term goals.

The third project presented was in Northamptonshire. Although not initially designed as cohousing, by the end of the codesign process, people leaned more toward collaborative living. The building group workshop allowed participants to play a role in designing their homes.

Meredith’s key take-away:

Codesign is a way to manage a mixture of idealism (the hope future can change for the better) and pragmatism (getting things done) . Developing sites is very complex; you need to be pragmatic; however, idealism can help the designer and community to hope that the future can change for the better”.

Meredith’s tips for codesign:

· Small groups work best.

· Summarise conversations at the end of each session.

· Gather feedback regularly.

· Uncover values through the process, as these may lead to unexpected outputs.

· Communities evolve over time, so having community skills embedded within the group is crucial to maintaining the culture of cohousing.

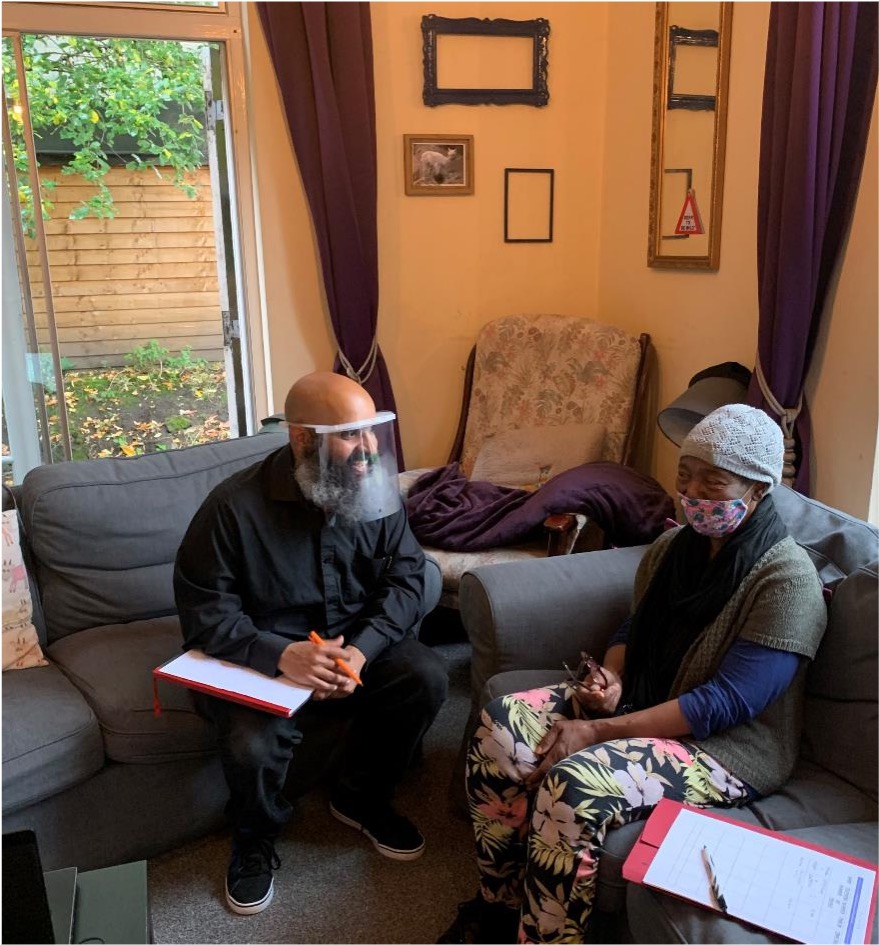

Codesign for social rental housing: Harry Randhawa, Triangle Architects

(Images above from Harry Randhawa’s presentation showing co-design work in action)

Harry emphasised that many people, especially those from underrepresented groups or who face language barriers, are often excluded from having control over housing design. Triangle Architects works with housing associations and minority communities, such as LGBTQ+, migrants, and ethnically diverse groups, to deliver affordable housing. However, Harry pointed out that reference materials for these projects, like “Accommodation Diversity” or “Ageing in Place for Minority Ethnic Communities” guides, are scarce and often outdated.

He stressed the need to better understand how minority groups live and age, and to track emerging trends. Housing 21, for example, has a strategy to develop 10 cohousing-inspired social rental projects for low-income communities across Birmingham, focusing on Bangladeshi, Pakistani, and Somali residents. Language barriers posed a challenge, so Triangle Architects introduced a pictographic methodology, using visual reference cards for room types to help residents engage with the process. Their feedback was integrated into the feasibility study, while keeping designs economically viable. Ultimately, residents sought secure, manageable, safe, and welcoming homes where their families and friends could visit.

Harry highlighted the importance of showing future residents a clear diagram to explain the collaboration process between them and the architects. Triangle Architects have also signed on to design a majority LGBTQ+ extra care housing scheme in Manchester.

Harry outlined Triangle’s approach to codesign in more detail in the following UKCN guide: Housing Associations and Cohousing; How to create inclusive, affordable, collaborative neighbourhoods for older people.

Harry, Meredith and Mellis form a panel to answer questions from the floor.

Codesign and Cohousing In the Netherlands, Flip Krabbendam and Tijmen Kuyper

Dutch cohousing goes back a long way, since the 1900s, with examples of Hofje van Bakenes – Haarlem and later on the Garden City Social Housing. Then, between the 70s and 90s, there was the Centraal Wonen. In the 80s, lots of squatting communities appeared, which have now been legalised. Mostly after the 00s collective self-build happened. And since 2015, new build coops as some laws changed.

From their perspective, the future is mixed, with many different types and hybrids of lifestyles (Sharing events, multigenerational, mixed cultural backgrounds, etc.) and Financial judicial variants (social rents, cooperatives, collective self-built, refugee housing, private rent, etc.).

Make or Break Factors for Dutch Cohousing:

· Location: Local governments select the plots.

· Finance: Subsidies and loans from banks and the government are essential.

· Knowledge: Networks, days of exchange, and excursions are vital for sharing how these types of projects are being developed.

Movement with momentum where books, media attention, television, etc. show that it is possible. This is creating a boost in the social movement. Despite its successes, there are still challenges for residents, government agencies, social housing corporations, and entrepreneurs. However, these challenges offer opportunities for learning and improvement.

How to design for engagement for cohousing?

1. CoWonen’s Fundamentals

Privacy: Control over access and the sense of having private and public areas.

Ownership: A feeling that the place or group belongs to you, and you have a say in it.

Click: Social and spatial “click” with those you share facilities with. People must have control over which shared facilities they want.

Casual Encounters: Unplanned interactions, which are seen as “the oxygen to society.”

Planned Interaction: Traditions and regular activities are important for fostering relationships.

Social Continuity: Valuable relationships develop over time, and informal care often stems from long-standing connections.

2. Transition Zones between scale levels are important, e.g., house and street.

Enable ownership where self-made ‘buffers’ – self-made ‘connectors’ allows for casual encounters between neighbours

3. Engagement with shared spaces

Attractive use for residents – Create something attractive for residents so that people spontaneously make use. Something there to bring people e.g., good coffee, something you have to attend to (vegetables),

Spatial hierarchy – Subdivide larger spaces so people don’t feel lost if they sit there themselves

Create alcoves and little nooks, something to enable the feeling that you are in a small space

Conversation starter – Triangulation principle. Get other people to use the space, e.g., a hole in the hedge so people can watch playing going on. Works in public space; at a bus stop, you can talk to people about the bus; looking at art/others playing / animals – interesting to talk about.

4. Circulation is communication

Making people move through spaces spontaneously, rather than by necessity, helps foster interaction. Examples include creating “pause places” along daily routes, like courtyards or hallways, where people can slow down and linger. However, not all routes should pass through public areas, as this can reduce privacy. Balancing privacy with opportunities for casual encounters is key.

Creating a “not-now route” (a more private path) helps provide a balance. Combine “must” (private household functions like litter containers) with “may” (optional activities like a shared garden or roof terrace). This ensures that shared facilities encourage people to visit other places within the community.

Amsterdam's New Co-operatives, Boris Zeisser, Natrufied

Boris presented “De Warren”, a cooperative housing project on Centrumeiland in Amsterdam, featuring 36 apartments for social and affordable rental housing. It is Amsterdam’s first self-build housing cooperative, developed on a floating island as part of a regeneration project. Inspired by cooperative housing models in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, a local government officer allocated a plot for a cooperative to develop a cohousing project. A group of young people, aged 25 to 30, pitched their proposal and secured the site.

This group had no funds, so they organised to obtain subsidies. They created a unique model between renting and ownership: while they collectively own the building, they cannot sell it, but they do have control over its management.

Boris’s team led five workshops with the group. The first focused on defining the purpose of the building, where they decided on two key goals: collective living and sustainability. Another workshop determined that 30% of the building should be dedicated to shared spaces, including a collective kitchen, auditorium, kids’ area, music room, co-working space, and greenhouse.

In a sustainability workshop, the team used a game developed by “Natrufied” to explore the cost vs sustainability trade-offs, helping the group make informed decisions balancing eco-friendliness and cost efficiency.

The building was designed for flexibility, accommodating both young people who enjoy social activities and those with families, fostering a harmonious living environment for both.

More about this process is documented in “Living Together: The Story of De Warren” currently playing in cinemas, awaiting release online. This case study highlights how one government champion can spark wider change. Today, 13 similar initiatives exist in Amsterdam. While challenges remain—such as banks being reluctant to fund early-stage projects—the government is working on initiatives to support cooperative housing projects like this one.

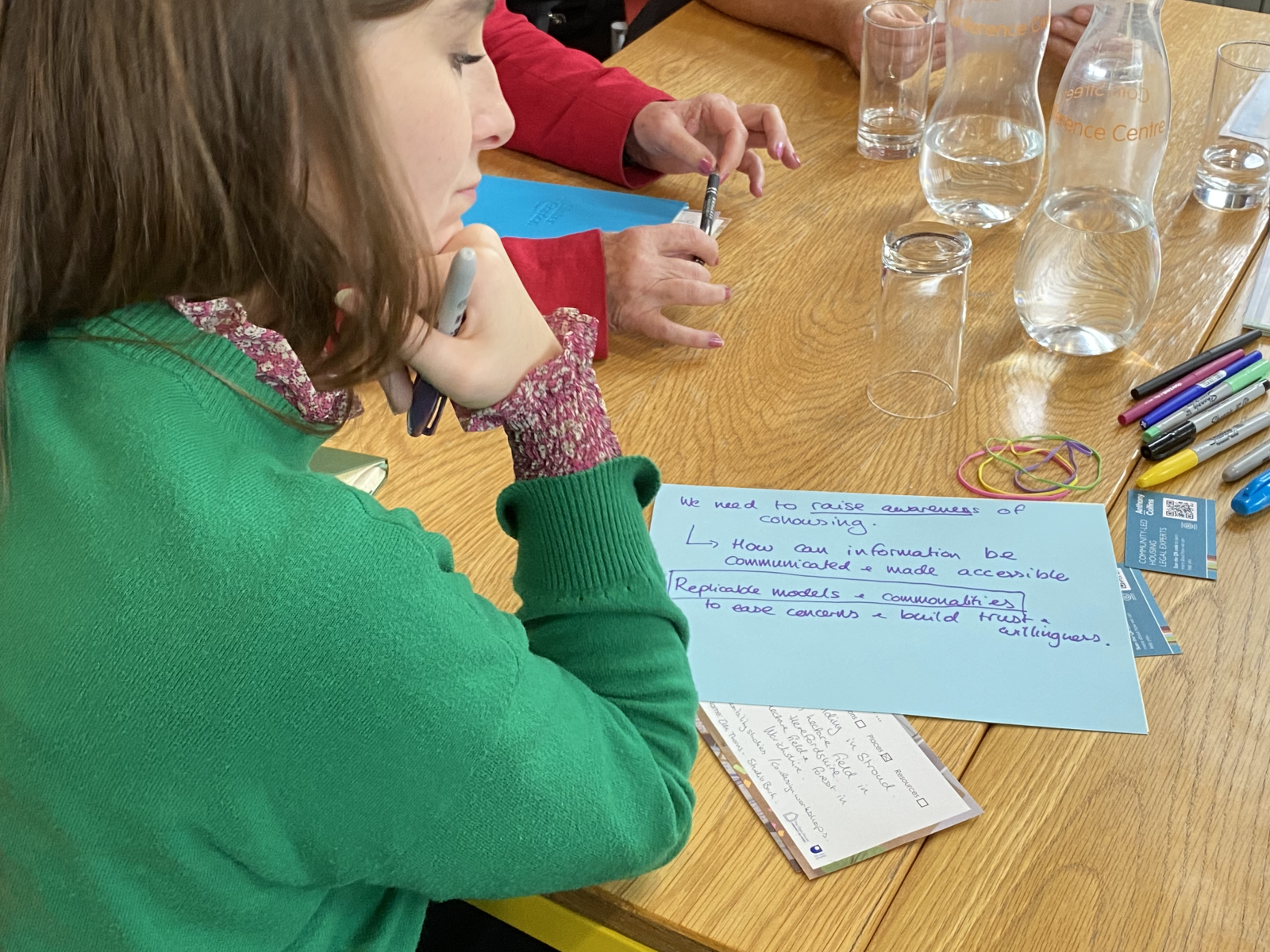

Cross-Pollination: The Glass-House, The Open University

Sophia De Sousa (The Glass-House), Louise Dennison (The Glass-House), Theodore Zamenopoulos (Open University), Vera Hale (Open University), Katerina Alexiou (Open University)

The Open University and The Glass-House team led a cross-pollination session, designed to foster trust, support, and collaboration. Participants shared current or future projects with others at their table, who then explored ways to offer support or collaborate. Attendees reported that the process was highly valuable, sparking new connections and encouraging a spirit of creativity and opportunity in the room.

Summary: why do we need codesign in housing?

A fishbowl discussion led by an initial panel of Maria Brenton, Dinah Bornat (ZCD Architects) and Jonny Anstead (TOWN) created a lively discussion as to the extent to which codesign was a key part of creating sustainable, thriving places to live. Some of the key points raised here and in the earlier discussions are captured below.

Post-event note: what is co-design? “Co-design is a well-established approach to creative practice, particularly within the public sector. It has its roots in the participatory design techniques developed in Scandinavia in the 1970s. Co-design is often used as an umbrella term for participatory, co-creation and open design processes. It reflects a fundamental change in the traditional designer-client relationship. The co-design approach enables a wide range of people to make a creative contribution to the formulation and solution of a problem” Design Europe

Codesign is taken to be a non-negotiable for successful cohousing communities. However, the whole day came to life when one participant challenged the room to consider whether codesign was indeed essential to good placemaking, particularly as it only involved the initial resident group and not future generations. A wide-ranging discussion continued. Some key points arising.

Assuming codesign process brings people together, making management and there was widespread support in the room for the view that it enhances the chance of long-term success.

Key discussion points for practitioners to consider:

The Design Process: community relationships are formed through the process of creating a vision for a community, designing a site, and the common spaces and private homes. Alongside improving the quality and “fit” of design to needs of the first generation of users, it also helps create a culture of participation and democratic decision making that can last generations.

· Accessibility and Futureproofing: good housing lasts, yet whilst we can’t always accurately predict the needs of future generations, we can design for adaptability and encourage enduring cultures of participation which enable future residents to respond to needs.

· Ethical Professionalism: codesign, as Mellis Haward put it, requires designers to park their egos at the door, placing users. Or as activists might put it – “nothing about us, without us”. Codesign, commits professionals to commit to ethical practices and be accountable.

· Risk to the Project: codesign aims to meet people’s needs in contrast to projects that make speculative assumptions, reducing risk of under-occupancy, loss of value, or mission drift.

· Genuine, constraints: whether the site, finance, timeframes, developer/HA/regulatory requirements or policies may affect when, what and how far codesign is feasible at points in the journey.

· Engaging Beyond the Cohousing Community: cohousing can make a genuine contribution to the quality of the wider neighbourhoods and the codesign process needs to consider non-residents in order to realise that potential.

· Planning Engagement: it is a truism that people only engage with the planning system by objecting. What if they felt empowered and had a sense of agency? Codesign methods are hugely under-used and could make a powerful difference to popular support and engagement throughout the planning process.

· Ambition: codesign may generate unexpected results that are unique and tailored to the community’s needs. This allows the design to be more ambitious and radical.

Considerations for a good Codesign Process

· Be Transparent: Discuss the steps of the process and what can be codesigned in each stage.

· Inclusive and Flexible Process: Codesigning effectively, tailored to the needs of those involved results in designs that are inclusive.

· Quality: and transparency of codesign process is key to achieving lasting, desired outcomes. Poor quality can damage reputation or lead to community-washing.

· Future-Proofing and Intergenerational Planning: we can start to accommodate future changes in the community by building adaptability into designs to benefit future generations.

· Cost Implications: whilst for many the ethical and business case for codesign is clear, both in the short and long-term, greater discussion, awareness and demonstration is needed to see it more widely adopted

Summit closes - where next?

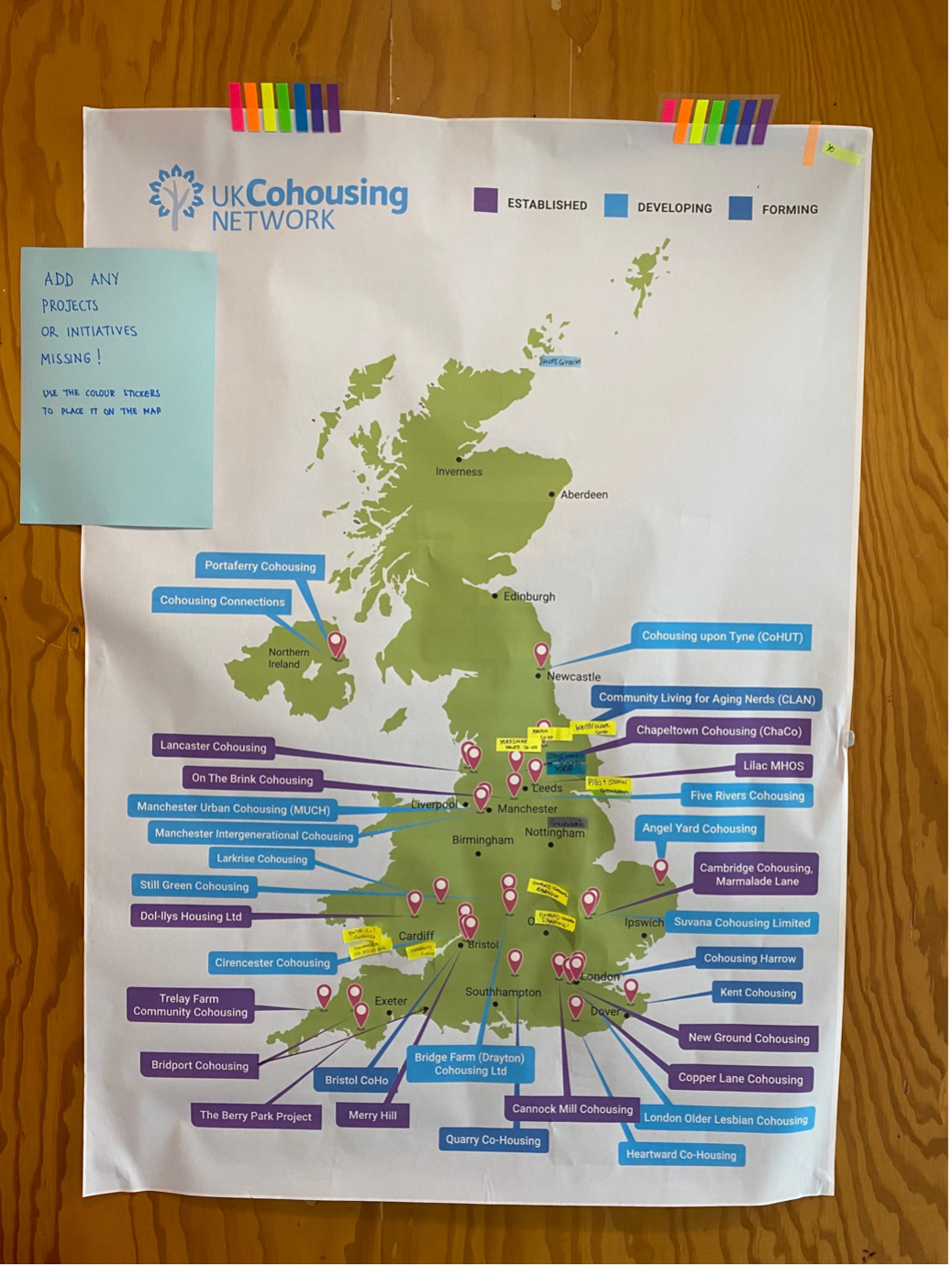

The UK Cohousing Network Summit 2024 closed to widespread applause in the packed room for the speakers, organisers and importantly all the participants themselves. During the day, participants had been invited to map their current and future projects on a giant map of the UK, populated with many of the UK Cohousing Network’s members. Participants left, better informed, better connected with many alliances created, ready to collaborate in the year ahead.

More from UK Cohousing Network

Want to keep the momentum going and build connections and alliances through UK Cohousing Network?

Here are some options to get you started:

UK Cohousing Network Newsletter: https://cohousing.org.uk/newsletters/

UK Cohousing Network’s Membership: https://cohousing.org.uk/sign-up/

National “waiting list” for cohousing opportunities: https://cohousing.org.uk/national-cohousing-register/

Reports, research and guides: https://cohousing.org.uk/publications-and-research/